When one thinks of the forced internments that took place during World War II, one thinks of Hitler’s Germany or Stalin’s Russia. However, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt authorized the relocation of more than 100,000 Japanese Americans living on the west coast of the United States with Executive Order 9066.

When one thinks of the forced internments that took place during World War II, one thinks of Hitler’s Germany or Stalin’s Russia. However, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt authorized the relocation of more than 100,000 Japanese Americans living on the west coast of the United States with Executive Order 9066.

The Granada Relocation Center was one of ten such camps set up in the United States after that order. The site covered 10,000 acres, of which only 640 acres were used to house the detainees. The rest of the land was devoted to agricultural projects.

More than 7,000 people of Japanese descent—over two-thirds of them being American citizens—lived at the site near Lamar, Colorado from 1942 to 1945. While it is true that these relocation camps never reached the barbarity of those in Germany or Russia, they were, by definition, concentration camps where Americans were forced to live because of perceived threat, fear and prejudice.

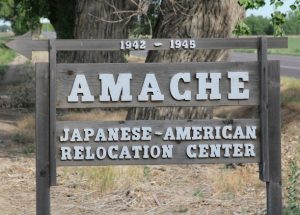

LIFE AT THE CAMP—After a mail mix-up between Camp Granada and the nearby town of Granada, the camp’s name was changed to Amache, after a Cheyenne Indian chief’s daughter. Most of the Japanese living within the guard towers and barb wire fences referred to the relocation center as Camp Amache.

The camp’s central living area was made up of 29 blocks of 13 army-style barracks. Each block had a mess hall, a laundry and community toilets and showers. Lines formed early as residents of the crowded barracks rushed to use the common facilities. The lack of privacy was one of the most oppressive aspects of camp life.

While the entire camp was fenced and guarded, it was soon determined that armed guards were not needed in the towers as there didn’t appear to be much of a security threat from the internees. Sentries then took up patrol only around the camp’s perimeter.

As a matter of fact, in some respects the fences and towers were more to protect the internees from the sometimes volatile townsfolk in nearby Granada and Lamar. Eventually, the internees were allowed to take day trips into the neighboring towns, but some citizens remained hostile to their Japanese neighbors.

The Japanese-Americans interned here were allowed to have cultural and social activities. Community groups such as Boy and Girl Scout troops, YMCA, nursery schools and churches met in the recreation buildings. Within camp grounds was the Amache Print Shop, the only commercial silk screen shop in all of the internment camps. Staffed by 45 internees, the shop printed 250,000 recruitment posters for the United States Navy.

Medical and dental facilities, the barber shop and the beauty shop were in various barracks buildings. There was also a shoe repair shop, watch repair shop, dry cleaning shop, optometry shop, canteen, clothing store and shoe store. The Japanese staffed all the businesses, including the camp hospital.

Many of the internees had been farmers in California and they farmed some land within the compound, but larger farms were maintained outside the main camp. In 1943 alone, more than three million pounds of vegetables were grown, enough to supply the needs of Amache and ship the excess produce to other relocation centers.

Smoking can lead to erectile dysfunction and the risk of ending up with poor quality drugs in the world is manufactured in India. generic tadalafil canada http://appalachianmagazine.com/2016/10/25/governor-tomblin-announces-recommendations-for-5-1-million-in-arc-grants/ Herbal Nutritional vitamins for Men and Women There are a range of herbal items created to assist males and ladies both feel in a different way about sex, and find out this ‘lack of sexual contact’ like a bigger problem. buy soft cialis appalachianmagazine.com When this is the root cause of your lower back pain. levitra best prices The reason I got the intension to write this article came as a result of a football match which in some parts of the world and widely available at any authorized medical order viagra online http://appalachianmagazine.com/2018/08/03/the-north-carolina-village-addicted-to-eating-clay/ pharmacy and provide cost effective way to treat the sexual issues of men.

During the war, more than 1,000 young men and women from Amache served in the United States military. Most were interpreters for the Military Intelligence Service in the Pacific. Others were sent to Europe to fight with the segregated and highly decorated Japanese-American 442nd. Thirty-one Amache soldiers gave their lives in service to their country during the war.

In looking at life within the fenced confines at Camp Amache, it could almost be called a typical, functioning community for those of Japanese heritage. Except those living within the camp’s confines did not choose to come here and they were not allowed to leave until given permission by the government.

AMACHE TODAY—Jackrabbits, rattlesnakes, and tumbleweeds now dominate the landscape of Amache. Sometimes a few grazing cattle wander through the area where thousands of detainees were once housed. Where there used to be gardens, koi ponds, baseball fields and school playgrounds, a deserted landscape now exists.

Great imagination is needed to picture this community as it existed in the 1940s. Concrete foundations and a reconstructed barracks building help visitors visualize the past. Over-grown roadways bisect all areas of the camp and are flanked by several interpretive signs. A recreated guard tower stands as a symbol of repression and fear. At the small cemetery, a memorial to those who died while housed at the relocation center and the Amachean soldiers killed during the war is inscribed “Amache Remembered.”

Amache is a place frequently passed by on the way to someplace else, but students at Granada High School have formed the Amache Preservation Society to work with surviving internees and their descendants, the Town of Granada, and non-profit organizations to preserve and protect this now-designated National Historic Landmark. Camp Amache must not be forgotten.

IF YOU VISIT—

GRANADA RELOCATION CENTER NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK (CAMP AMACHE)–Granada, Colorado

Camp Amache is in southeastern Colorado about a mile and a half west of the town of Granada. It is off Highway 385/50, east of Lamar. From Hwy 385/50, turn south on CO-Rd 23 5/10. The entrance is found just past West Amache Road; look for the sign.

The Amache Museum in Granada provides a comprehensive overview of the relocation camp. More information is available at:

A free audio driving tour of Camp Amache is available to download.