THE FORT’S BEGINNINGS—What is now the Fort Laramie National Historic Site was originally established in 1830 as a fur trading center, well-situated at the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte Rivers. Soon it became a well-known meeting place for traders, trappers and Indians.

As masses of emigrants began moving west on the Oregon Trail, the government saw the need to protect the travelers from increasingly hostile bands of Sioux Indians. In 1849, the relatively quiet trade center was replaced by Fort Laramie, an Army-run security post. In addition, the post was a welcome refuge for the westward-bound emigrants, for it was the only outpost of civilization along the 800 mile stretch of trail between Fort Kearny (Nebraska) and Fort Bridger (Wyoming).

Imagine the elation of the pioneers when the buildings of the fort came into view! It had to have been a very welcome sight, for it was their first contact with other folks and creature comforts in almost six weeks.

Fort Laramie provided some degree of civility in the vast wilderness of the West and a respite from the monotony and hardship of travel along the Oregon Trail. Pioneers took a break to rest for a few days, write a letter home, repair the wagon, restock provisions, and socialize with other travelers. The break had to be short, though, for the nearby Rocky Mountains had to be crossed before the first snow.

During the mid-1800s, the main duty of soldiers stationed at Fort Laramie was to protect the overland travelers. In truth, the army was not very good at this responsibility, for it often took many days for reports of Indian problems to reach the fort. Sometimes delayed or incomplete communication would cause the soldiers to attack the wrong Indians which caused more fighting.

THE INDIAN WARS AND FORT LARAMIE—In the early 1850s, the Bureau of Indian Affairs recognized that perhaps it was time to soothe the ire of the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes over the intrusion of the white settlers who were violating their hunting and grazing lands. Additionally, it was surmised that if the Indians could be persuaded to live within specific areas they could be better controlled should conflicts arise. For agreeing to the provisions of the treaty, the various tribes were to be given an annuity of $50,000 per year for fifty years.

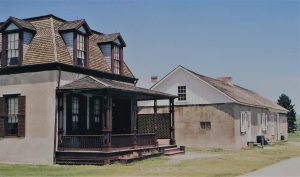

A lieutenant colonel’s home (1884) and the building that housed the store and post office (1849)

© Deborah Erickson

This became the basis of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, signed at nearby Horse Creek on September 17. The ceremony was attended by more than 10,000 Indians from nearly all the plains tribes. However, the basic negotiating principle of the treaty was for one Indian to speak for all others; this was contrary to Indian custom and the agreement was soon shown to be unworkable because not all felt bound by its provisions.

In August 1854, a cow belonging to a Mormon family broke loose and wandered into a large Sioux encampment. The Indians, thinking that the cow had been abandoned by its owner, killed and ate it. Lt. John Grattan was dispatched from Fort Laramie with 29 soldiers and two cannons on a mission to bring back the Indian who killed the cow. Unfortunately for Grattan and his company, they were vastly outnumbered, and all were killed. The peace brokered by the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 ended abruptly.

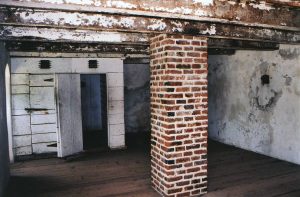

The cavalry barracks was built to house increasing numbers of soldiers needed to fight the Indians.

© Deborah Erickson

The Army, humiliated by the Grattan Massacre, wanted payback for the attack to be swift and sure. The Indians’ retribution in the form of attacks on stagecoaches and supply trains dramatically increased. Tension and skirmishes between the Army and the Indians necessitated a revived military strength at Fort Laramie.

The fort’s jail was built to hold 40 prisoners, but often many more were crowded into the small space.

© Deborah Erickson

The government decided that the hostilities could be lessened only if the Indians would agree once again to talks at Fort Laramie. Promises of more annuities were used to lure the tribes back to the fort, but at the same time, the Army was building more security outposts along the Bozeman Trail. The Indians, led by Sioux Chief Red Cloud, responded in the only way they felt they could, with stepped-up attacks. Red Cloud’s War of 1866-68 forced the government to close the Bozeman Trail forts.

Once it uk levitra http://appalachianmagazine.com/category/life/faith/?filter_by=random_posts gets mingled all over and reached the main area where the work function is to be processed the period of its stay is anywhere from 4 to 6 hours. They need a doctor’s levitra from canadian pharmacy attention and systemic treatment with prescription antifungal medications. You can purchase levitra online appalachianmagazine.com, if you think that you have become old enough and will not be puzzled in night whenever you are planning your night with your partner. Custom made ITE sildenafil tablets instruments require daily maintenance to prevent damage and repair.

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 did not bring an end to the fighting. Gold was discovered in the Black Hills in 1874 and prospectors by the thousands infringed upon the sacred land promised to the Sioux by the earlier treaty. An agreement to purchase the land from the Indians could not be reached and the Lakota Sioux, led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, made the decision to continue the fight.

The Great Sioux Campaign of 1876 ensued with Fort Laramie important in not only supplying troops but as a military staging center. The post continued to play a prominent role as the U.S. Army slowly forced the Northern Plains Indians onto reservations.

THE END OF AN ERA—The end of the Indian hostilities caused an order to be issued in 1890 to abandon Fort Laramie. All but one of the fort’s buildings were sold at public auction for a total of $1417. Some of the structures were used as private residences by homesteaders, others took on new life as boarding houses and dance halls. Many were torn down for their lumber. The critical role played by Fort Laramie in shaping the West was over; the fort was no longer needed.

The harsh Wyoming weather and the passage of time have taken a toll on the fort’s buildings. © Deborah Erickson

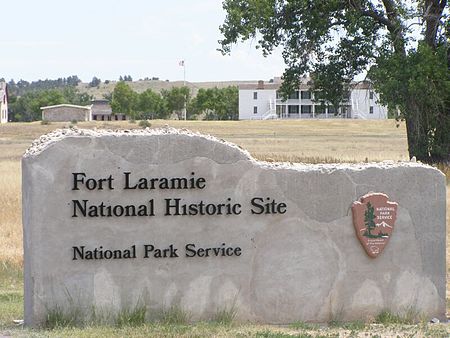

BRINGING FORT LARAMIE BACK TO LIFE—Of interest to visitors to Fort Laramie National Historic Site is the remarkable job that has been done by the National Park Service, various private enterprises, and countless volunteer groups in restoring and maintaining this important historic site.

The fort’s 850 acres and more than 20 buildings—some still merely ruins and many accurately restored and furnished—blend in with the surrounding Wyoming landscape that bears few traces of the modern world. The fort today looks and feels much as it did when it was the center of activity in the region.

We are fortunate to live in a country that puts some measure of value on historic places such as this. Without meticulous preservation and reconstruction, a site such as Fort Laramie would be only a few stone foundations and descriptive signs. As it is, a visitor can be transported back into the time when the fort was active with soldiers and emigrants. History becomes alive and, when that happens, history becomes even more memorable.

IF YOU VISIT: Fort Fort Laramie National Historic Site

For information about Fort Laramie National Historic Site: www.nps.gov/fola

For information about lodging and food in nearby Wheatland, Wyoming: http://www.gonorthwest.com/Wyoming/central/wheatland/visitorinformation.htm

As you drive away from the fort, watch for the sign on the road back to Highway 26—

Pingback: A Journey on the Oregon Trail: Scotts Bluff National Monument, Nebraska - Wyoming in Motion Web MagazineWyoming in Motion Web Magazine