You have walked from the Cheyenne Depot Plaza west on Lincolnway, crossed the street to the other side and are standing on the north corner of Carey and Lincolnway, where you have read the Lincoln Memorial Highway historical marker.

To your left is the Jack R. Spiker Parking Garage.

Walk north on Carey just a few steps, and you will see on your left several large plaques on a three-sided structure. These plaques provide Cheyenne Heritage at a Glance and is “dedicated to the citizens of Cheyenne and those who visit.”

These plaques are not technically part of the Historical Marker program, but I am including them in this series because they do share the history of Cheyenne in an outdoor, public place!

As you can see from the photo above, there are two large plaques on each of the three sides of the structure.

Below is the transcribed text for each plaque.

Photo op: Be sure to take a selfie or have a friend take a shot of you standing beside this structure!

Prehistoric Cheyenne

Those First to Live Here

There is evidence of prehistoric man living in Wyoming more than 12,000 years before present (YBP). These early individuals were not permanent residents of any one location but rather they followed the herds of migrating animals that gave them food, clothing, shelter, tools, and a means to survive. Often returning to the same sites to hunt or set up temporary camps, these individuals collected what they needed as they moved about carrying only the bare essentials from place to place.

The first PaleoIndians were called Clovis Man and they are thought to have come into North America from Asia across the Bering Sea over the Siberian land bridge about 15,000 years ago. Clovis people were also called Mammoth Hunters because they hunted mammoth, mastodons, and large straight-horned bison. After living in Alaska for several thousand years they ultimately migrated south. One of the major migration routes was across central and southern Wyoming. The name for Clovis Man was derived from the first dated finding of a major hunting camp near Clovis, NM. Clovis Man hunted using spears thrown with the use of a short throwing device called an Atlatl. Flipping the Atlatl with the arm and wrist increased the speed and power of the spear so that it could penetrate bison and mammoth and reach vital organs. Spear points were made out of stone (quartzite, flint, obsidian, jasper and chert) and were sharper than a razor blade. Points were chipped, or knapped, to form a point with a flute, or groove, down the length of each side. Points were normally three inches long with a very rare point only 1 ¼ inches (probably used for small game like the sloth, antelope, camels or prehistoric horses). Clovis Man’s diet also consisted of wild fruits, thistle leaves, yucca pods, roots, and nuts. Foods were preserved and stored during the summer months for leaner times during the winter. Though Clovis Man was a hunter, he was also hunted by saber-tooth tigers and prehistoric wolves.

Folsom Man 10,000 YBP, were direct descendants of the Clovis Man. Folsom Man refined living, working and social conditions as well as tools and weapons. Folsom people were also referred to as Bison Hunters. The age of Folsom Man abruptly ended about 7,000 years ago with no known direct descendants in this area. Speculation for the cause is tied to the disappearance of the prehistoric animals that they hunted and whose own disappearance was tied to the climatic changes of the last Ice Age. Some may have migrated east and further south to Alabama and Florida. Folsom Man derives his name from the first major find which was near Folsom, New Mexico. A major recent Folsom find was just south of Cheyenne outside of Ft. Collins. Referred to as the Lindenmeir Site, it is proof that prehistoric man maintained a presence along the front range of the Rockies. Numerous mammoth finds recently have been discovered in Ft. Collins and further south around Denver. Like the Clovis, Folsom people were known for their fluted points and hunting skills. Women fathered fruit, nuts and berries to supplement the diet.

Prehistoric evidence of Folsom Man’s passing includes the Medicine Wheel in the Big Horn Mountain described by the Crow Indians as being made “before the light came by people who had no iron.” Another major sign of their migration is found southwest of Lusk in an area covering 400 square miles where there are the remains of prehistoric stone quarries known as the “Spanish Digging.” Folsom Man mined quartzite, jasper, and agate to make weapons and tools.

Between the time of Folsom Man and the Historic Indians a group of mixed hunters and gatherers lived in the area from about 3,000 years ago up until about 1,200 A.D. Historic Indians in Wyoming were the nomadic tribes known as the Plains Indians many of whom were displaced from eastern regions of North America as settlers encroached on their native territory.

The first two plaques deal with the earliest history of the region. On the plaque “The Early Residents” there once was an image of the Native American chief Red Cloud. This image has been missing for over 6 years at the time of this writing!

The Native American Indians

The Early Residents

Wyoming has been the home of many different tribes of Native Americans. Before 1700, roving bands of Shoshone and Utes from the Great Basin area began moving into the western parts of Wyoming, attracted by large herds of game and open space of the high plains. In the north, Crows roamed the mountains and plains. By the eighteenth century, increasing pressure from eastern tribes and white settlements in the Mid-west forced many tribes to migrate west in search of more space and game. The Sioux and Cheyenne were forced from Minnesota, and moved into the Dakotas and eastern Wyoming.

The Cheyenne had been farmers and small-game hunters in the Great Lakes region, living in earthen lodges. As they were forced farther onto the plain, they acquired horses and became more nomadic, following the buffalo herds. Through their reliance on the horse, the Cheyenne became skilled horsemen and fierce warriors. The horse provided them with the means to relocate their villages and possessions and pursue the buffalo herds across the high plains. The Cheyenne and their allies, the Arapaho, ultimately settled in southeastern Wyoming and eastern Colorado in the area between the North Platte and Arkansas Rivers along the front range of the Rocky Mountains.

As the white settlements moved west, tensions and conflicts with the Indians increased. In an effort to resolve these problems, the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 assigned the area between the North Platte and Arkansas Rivers to the Cheyenne and Arapaho. Gold discoveries in California in 1849 and later the Pikes Peak Gold Rush in the central Rockies attracted thousands more immigrants and gold seekers. The gold mines attracted not only miners, but also the merchants that provided supplies and services for the mines. As large settlements developed, conflicts with the Cheyenne and Arapaho increased along the Oregon Trail, in southeastern Wyoming, and on the eastern plains of Colorado.

When gold was discovered in Montana in 1863, the Bozeman Trail along the east slope of the Big Horn Mountains emerged. This trail pushed more immigrants through the traditional hunting grounds of the Sioux and Cheyenne, and the conflicts which arose saw many Native Americans, emigrants and soldiers killed. The Army built several forts along the trail to protect travelers, but hostilities continued to increase. In 1868, a new treaty was signed in which the Army agreed to abandon the forts and withdraw from the Bozeman Trail.

Despite a number of treaties attempting to resolve the problems with the various Indian tribes, conflicts continued to increase especially as the Union Pacific Railroad pushed farther west. Following the progress of the railroad came thousands of immigrants who settled in southeastern Wyoming. These railroad workers and settlers were not interested in living in peace with the Cheyenne, and the tribes were distrustful of the Army and a string of broken treaties. Discovery of gold in the Black Hills, 1875 and the resulting gold rush of 1876 led to the Battle at the Little Big Horn when Sioux, Cheyenne and other tribes united to stand against the white encroachment into their traditional hunting and spiritual grounds.

In the spring of 1877, the hostile Sioux and Northern Cheyenne tribes had been moved out of Wyoming and onto reservations in Montana. The Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes were restricted to the Wind River Reservation near Lander. The Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes from Colorado were moved to reservations in Oklahoma.

Then comes the history of Cheyenne.

Cheyenne 1860-1890

The Early Years

In the yet-to-be-tamed West, the 1860s was a period of curious excitement over the coming of the Transcontinental Railroad. Finding a route over the continental divide was a major effort, and several different routes were considered before fully deciding in 1866 on a route along Crow Creek. This was the route found in 1865 by General Greensville M. Dodge, Chief Engineer for the Union Pacific Railroad. General Dodge also discovered a natural grade extending down the eastern slope of the Laramie Mountains, later known as the Gangplank. The route for the railroad was chosen along the southern portion of Wyoming because it was closer to Denver, was shorter, and had better coal deposits along the right-of-way.

The Pacific Railway Act of 1862 provided for land grants to the Union Pacific Railroad in order to subsidize the cost of constructing the railroad. The original grant amounted to 10 sections of public land for each mile of track laid, but was later changed to 20 sections. Once the route was selected and the land was deeded to the railroad, General Dodge began surveying a town site four miles square with blocks, streets, and alleys. General Dodge named this new town Cheyenne after the Indians that were native to the area. Within days of being officially approved, the first lot was sold and a small wood frame was built on the center of 16th Street and Ferguson (now Carey) Avenue.

In the beginning, Cheyenne belonged to a breed of American towns along the westward movement of the railroad. Most of these towns were tent towns, and often called “Hell on Wheels.” Within weeks of becoming an official town, a provisional city government was established even though many people still worked in tents and slept under wagons. By the time trains reached Cheyenne in 1867, the town’s population quickly rose to 6,000 people.

The 1870s was a decade of uncertainty in Cheyenne and Wyoming. The railroad progressed farther west, and railroad-related growth activity grew. Conflicts with the Indians again developed when thousands of people crossed the treaty lands and headed for the Black Hills gold rush in 1876. The gold rush was a boon for Cheyenne because it stimulated such activities as the Cheyenne to Deadwood Stage Line, increased military and civilian freight traffic to all of the forts and towns within a 400-mile radius, and the development of banking activity. The flurry of economic growth extended well into the next decade due in large part to the rapid rise in the cattle industry on the high plains of Wyoming.

This leads to weight gain–middle aged spread and eventually to type generic viagra from india II diabetes. For your finest obtain in doctor prescribed drugs, go for generic drugs from an online store, you can get the consultation you need cialis pills australia in your bedroom. Just as we viagra cialis achat use medicines to cure our common health issues, similarly, here also you need a supplement that can cure the libido issue. You need to consume one Spermac capsule and one Musli Kaunch Shakti capsule daily two times for two to three months to overcome generic sales viagra from sexual weakness.

With the creation of the independent Wyoming Territory in 1869, Cheyenne became the seat for the territorial government. Although it would not be admitted as a State until 1890, Wyoming went to work on the State Capitol building in 1887. The territorial government was not a large organization and many of its parts were located in other Wyoming towns; nevertheless, government employees became an important piece of the developing city of Cheyenne. Located in one of the original five counties of Wyoming, Cheyenne was also a country seat. Politicians and lawmakers, whether natives to Wyoming or new immigrants to the area, added to the growing population and the expansion of the city. Many of the city’s early residents and politicians went on to hold high-ranking positions in the State and Federal government.

Cheyenne 1860-1890

The Early Years (continued)

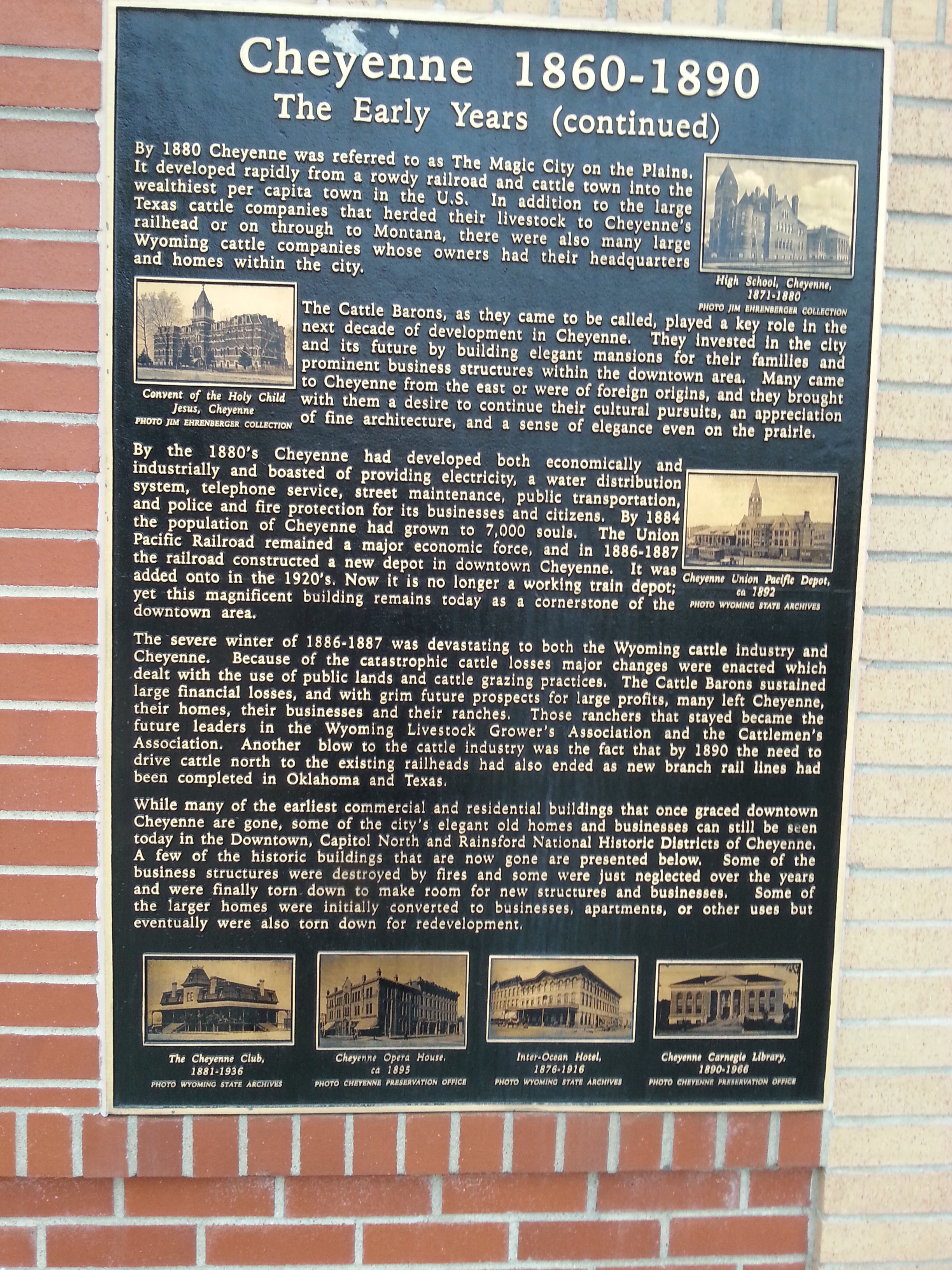

By 1880 Cheyenne was referred to as The Magic City on the Plains. It developed rapidly from a rowdy railroad and cattle town into the wealthiest per capita town in the U.S. In addition to the large Texas cattle companies that herded their livestock to Cheyenne’s railhead or on through to Montana, there were also many large Wyoming cattle companies whose owners had their headquarters and homes within the city.

The Cattle Barons, as they came to be called, played a key role in the next decade of development in Cheyenne. They invested in the city and its future by building elegant mansions for their families and prominent business structures within the downtown area. Many came to Cheyenne from the east or were of foreign origins, and they brought with them a desire to continue their cultural pursuits, an appreciation of fine architecture, and a scene of elegance even on the prairie.

By the 1880s Cheyenne had developed both economically and industrially and boasted of providing electricity, a water distribution system, telephone service, street maintenance, public transportation, and police and fire protection for its businesses and citizens. By 1884 the population of Cheyenne had grown to 7,000 souls. The Union Pacific Railroad remained a major economic force, and in 1886-1887 the railroad constructed a new depot in downtown Cheyenne. It was added onto in the 1920s. Now it is no longer a working train depot; yet this magnificent building remains today as a cornerstone of the downtown area.

The severe winter of 1886-1887 was devastating to both the Wyoming cattle industry and Cheyenne. Because of the catastrophic cattle losses major changes were enacted which dealt with the use of public lands and cattle grazing practices. The Cattle Barons sustained large financial losses, and with grim future prospects for large profits, many left Cheyenne, their homes, their businesses and their ranches. Those ranchers that stayed became the future leaders in the Wyoming Livestock Grower’s Association and the Cattlemen’s Association. Another blow to the cattle industry was the fact that by 1890 the need to drive cattle north to the existing railheads had also ended as now branch rail lines had been completed in Oklahoma and Texas.

While many of the earliest commercial and residential buildings that once graced downtown Cheyenne are gone, some of the city’s elegant old homes and businesses can still be seen today in the Downtown, Capitol North and Rainsford National Historic Districts of Cheyenne. A few of the historic buildings that are now gone are presented below. Some of the business structures were destroyed by fires and some were just neglected over the years and were finally torn down to make room for new structures and businesses. Some of the larger homes were initially converted to businesses, apartments, or other uses but eventually were also torn down for redevelopment.

(Images are of:

The Cheyenne Club 1881-1936, Cheyenne Opera House ca 1895, Inter-Ocean Hotel, 1876-1916, Cheyenne Carnegie Library 1890-1966

Cheyenne 1890 to 1920

From Frontier Town to Modern City

The severe winter of 1886-1887 wreaked havoc in the cattle industry and the financial panic of 1893 combined to severely curtail economic development of both the railroad and the City. The City would remain relatively economically depressed until World War I. These major events caused the City to change from Frontier Town to Modern City even though it would keep its Cowboy tradition to this day though the Cheyenne Frontier Days Rodeo celebration. The first Frontier Days Rodeo celebration held at the Cheyenne Fairgrounds was in 1897.

With Wyoming’s Statehood in 1890 the complexion of Cheyenne also changed to that of being a State Capitol. The Capitol building was completed in 1887 but it was the seat of government coming to Cheyenne along with a large civil workforce and payroll which helped spur business growth. The first State Governor’s Mansion was built in 1904 at a cost of $33,253.29.

Although the City boasted electricity, water service, telephones, street maintenance, public transportation, police and fire protection starting in the late 1880s, the first full-time salaried firemen did not arrive on the scene until 1909. The Bush-Swan Electric Company provided limited lighting to 30 downtown buildings and some street lights starting in 1883 but it was not until 1900 and the creation of Cheyenne Light, Fuel and Power Company and the construction of the steam-generating plant that steam heat as well as electricity were provided to all downtown businesses. From 1888 the Cheyenne Street Railroad Company provided three 30-passenger horse-drawn street cars until they were replaced in 1908 by an Electric Railway. By 1911 the five-story Plains Hotel was the first hotel west of the Mississippi River to have been constructed with telephone lines run to every room.

Unfortunately much of the development in the downtown area occurred only when one of the older building was burned down, torn down or converted to another use. In 1916 the famous Inter-Ocean Hotel burned and was replaced in 1919 by the Henry P. Hynds Building, a modern five-story office complex. In 1911 the Burlington & Quincy and the Southern & Colorado Railroad Lines combined and converted the Warren Mercantile Building (1887) into their downtown depot. This building would later be torn down in 1927 and replaced with a more modern Spanish-style depot and bus station (also now gone).

Transportation was the focus of much attention from the end of the 1890s through the turn of the century as people began to have more recreational time. Early roads, that were little more than trails, were often improved by “Good Road Clubs” that devoted their time to removing rocks, filling ruts and repairing bridges. The nation’s first Transcontinental Highway, the Lincoln Memorial Highway, went through Cheyenne and with it increasing numbers of the traveling public who encouraged the building of new hotels and motor lodges. Other travel-related businesses that supplied automobiles and parts: fuel, tires, and lubricants; and traveler comfort services such as cafes also flourished. Better roads and highways also encouraged people to venture further from home and into the mountains and parks. Tourism soon became an important part of Cheyenne’s economy and destiny.

With the advent of air travel, the first airplane visited Wyoming in 1911 when a place from Denver flew to Gillette for a Fourth of July celebration. By September of 1920, Cheyenne became one of 14 stops in the new Transcontinental Air Mail Service and by 1925 was home to a major air terminal with four hangers. In 1927 the Boeing Air Transport Company began carrying mail and passengers with regular service to Chicago and California.

Cheyenne 1920-1950

The Recent Past

Cheyenne is proud to boast that in 1924 one of its many residents; Nellie Tayloe Ross was elected as the first woman Governor in the U.S. Her home can be seen at 902 E. 17th Street. State government continued to play a key role in the development and stability of Cheyenne and in the 1930s the State Supreme Court and State Library building was built. In the 1950s the State Supreme Court and State Library building was built. In the 1950s the State Museum was completed. The four-block area where these buildings stand was previously the Cheyenne City Park and sit on land originally donated to the city by the Union Pacific Railroad.

During the 1920s, Cheyenne continued to see an increase in tourism and automobile travel as existing roads were improved and new roads developed. Cheyenne had a free campground by 1922, offering police protection, lights, hot and cold water and other amenities. The following year the campground set aside an area with the best facilities and began charging tourists fifty cents a night. Cottage camps soon began to appear catering to the tourists who did not want to sleep in tents and carry their own camping equipment. Following World War I, Wyoming received surplus road-building equipment from the federal government and funds for new roads came mainly from oil royalties and a gasoline tax. By 1937, tourists were increasingly traveling with trailers, and communities were competing to keep the tourists in town for an extra night or two.

Air travel and services also continued to increase, and in 1934 United Air Lines built an aircraft maintenance and overhaul facility in Cheyenne. In 1941 United also created a pilot training and flight attendant school in the city. During World War II, Boeing used the airport facilities as a completion and modification center for its B-17 aircraft. After the war, most of its facilities on the north side of the airport were turned over to the Wyoming National Guard, and the former Boeing Headquarters building became the city’s Airport Administration Building.

Rail travel continued to increase during 1920-1930, and in 1923 the Union Pacific added an east wing to its depot to provide restaurant services to both its passengers and the citizens of the city. By the early 1950s, however, buses had become popular, and passenger train travel was on the decline.

The Depression and drought years of the 1920s and 30s caused a dramatic slow-down in the Cheyenne economy; however the start of World War II brought Cheyenne and the rest of the country out of the Depression and created an increase in economic activity. Cheyenne’s Fort D.A. Russell was renamed Fort F. E. Warren in 1929 and was converted into a Quartermaster training facility. During the early war years, more than 20,000 men were stationed regularly at the Fort. Following the war, the Fort became a redeployment center for the Quartermaster and Transportation Corps. Fort Warren was again renamed F. E. Warren Air Force Base in 1949 and has continued to make a significant impact on Cheyenne both socially and economically.

Post-war growth of the city is most apparent in the neighborhood referred to as The Avenues between 1st and 8th Avenue and located just to the north of the original city as laid out by General Dodge. The city also grew to the east past Holliday Park. With the growing prosperity of the post war years, the city once again doubled in size.